Under the assumption that civic engagement is the primary vessel through which individuals exercise their political power, promoting collective participation is paramount in aspiring to a representative government. It follows that democratic governments ought to encourage and facilitate political participation while endeavoring to obviate any obstacles.

In contrast to her fellow democracies, America’s electoral process is notably burdensome on the voter. Here, a typically one-dimensional process is instead twofold: qualified individuals must first register themselves and then cast their ballot. Moreover, an overwhelming majority of states currently enforce restrictive laws that overcomplicate and discourage participation in the former, which consequently depresses turnout of the latter — and disproportionately affects the socioeconomically disadvantaged.

Of the most common and consequential requirements is closed registration deadlines; recent estimates claim that three to four million eligible voters were unable to cast a vote in the 2012 and 2014 presidential elections due to arbitrary registration deadlines.

Understanding the depressive effects of these registration laws requires the establishment of three preeminent grounds on which such criticism stands.

Firstly, facilitating the registration process tends to increase overall participation in the registration process. Assuming that individuals approach the decision to cast a ballot rationally, they must determine that the benefits outweigh the costs — and for marginalized communities these costs far outweigh the benefits.

Particularly suboptimal levels of political efficacy suggest that people already view voting as a low-benefit activity and are thus increasingly sensitive to additional costs or inconveniences associated with voting. Having to carve out time to commute to possibly different polling stations on separate occasions imposes a far greater cost on individuals with demanding schedules; all too often people cannot afford to register and vote if the process entails taking off work or school. Logistically, reducing the initial costs in the registration process encourages greater participation.

Secondly, the probability that an individual cast a ballot is corollary to their registration status — voter turnout in 2016 was 86.8% for registered voters as opposed to only 56% for all eligible voters. If an individual is registered to vote, they are more likely to do so. Furthermore, in the 2018 midterm elections, the four states with the highest turnout had liberalized voter registration laws — most prominently, Election Day Registration — EDR states’ turnout rate (56%) exceeded non-EDR states (47%) by seven percentage points.

Lastly, state governments ultimately wield the power to eliminate or at least significantly reduce the costs of voting — regarding the burdens in registering — and effectively expand the electorate and empower eligible voters.

Contemporary registration laws were, in part, enacted to ensure integrity and genuine interest in the electoral process. Integrity in the sense that registration laws supposedly provide a system of accountability, theoretically preventing ineligible persons from voting, casting multiple votes, and other forms of voter fraud. Additionally, many registration laws require voters stay keenly aware of deadlines and potential changes in re-registration dates; such measures were instituted to “purify” the electorate by ensuring only those interested and informed are granted the opportunity to vote.

Integrity and democracy should endeavor to work in concert, not contest — yet improving electoral integrity and voter accessibility have recently been subject to partisan debate. Of late, state governments tend toward the ends of the electoral-law spectrum: promoting accessibility, potentially sacrificing integrity, to securing integrity, and disenfranchising eligible voters. In the promotion of democratic values that include both integrity and voter accessibility, the defense for the current system evidently falls short.

Voter fraud is an illegitimate grievance; it poses no systematic threat to the electoral process. Current estimates indicate that at most only one in 4,000 votes cast in 2012 were double counted. The improbability of voter fraud may surprise many who report that double voting is a genuine concern. Public reporting is largely at fault for these sentiments — specifically a failure to differentiate between (1) registration records sharing common observable characteristics, (2) duplicate registrations, and (3) double votes. Additionally, inflammatory rhetoric, partisan fearmongering, and the mass spreading of misinformation have unsurprisingly resulted in wide-spread distrust in the electoral system.

Aside from addressing political inequity, liberalizing the registration process largely entails updating an outdated system. Newer computerized databases ironically render the current system obsolete; as systems computerize, voter registries should not be the exception. A computerized system offers a virtually impenetrable defense against the near mythical occurrence of voter fraud. For instance, the newer system can, in a matter of minutes, cross-reference voter registration information with other forms of identification like motor vehicles or Social Security databases, which are also entirely computerized.

Upon careful consideration it is evident that committing to the elimination of all unnecessary obstacles only enhances democracy. Conversely, in addressing the origins and antiquated provisions of the current system, it becomes evident that current restrictive registration laws blatantly undermine democracy at the expense of ineffective policy.

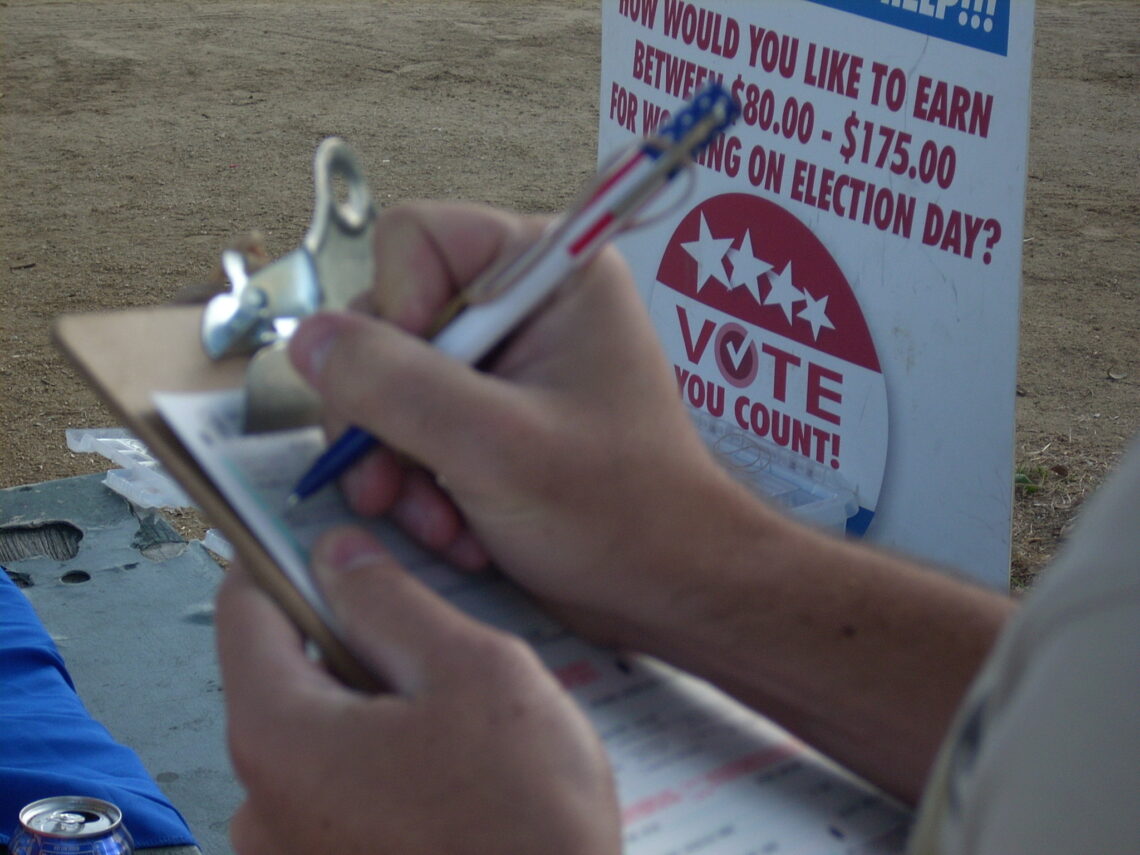

Featured image: Voter registration. Unmodified image by PlayCity used under a Creative Commons license. (https://bit.ly/2JwrYUp)

Check out other recent articles from the Florida Political Review here.